Posted in: 04/14/2023

To understand the importance of sustainability and achieve environmental justice , it is necessary to understand that sustainability is a state of balance between natural resources and our needs ; between Earth and humankind. Achieving a state of true sustainability, a material balance that truly protects natural resources and ecosystems , will only be possible through ethical, social, political and economic standards . The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were initially designed with this intention in mind.

The distinction between what is and what should be , is crucial in identifying the variables in search of this balance so as not to lose the transversal nature of the condition of the environment and interface with policies — health, agriculture, industry, urban and leisure —, that focus on a given reality.

In our country, it is known that – since the colonial conquest, passing through the occupation of land, the exploitation of resources by the Portuguese metropolis and the interstitial formation of a domestic market – the work of many people made a private territory for few of them .

With the advent of the Land Law , in 1850, and the establishment of capitalist social relations , private property over the territory and its resources became a basic condition for the exploitation of free labor ; outlining two processes that characterized the environmental frontier from then on:

These two processes, whether associated with extensive or intensive accumulation, gave rise, in turn, to the opening of social resistance fronts . Struggles over land, water and forests certainly preceded the environmental question as it is formulated. It was, however, from the beginning, about struggles for alternative ways of appropriating the material basis of society.

The environmental discourse later came to incorporate these struggles, giving rise to different perceptions and strategies, new arguments and projects in the public debate. Such struggles, along with concerns on the part of the world’s elites with the problem of “ limits to growth ”, ended up stimulating, in Brazil, an environmental discourse of “ governmental scope ”.

Therefore, the explicitness of the environment as an object of policies on a global scale is recent. The socio-environmental frontier goes beyond legislative issues related to municipal, state and federal legislation, precisely because it is a challenge for legislation .

Contrary to what we understand as environmental justice , there is a certain myth that environmental problems are above the interests of economic classes and the conflicts generated by these different interests . Air pollution , for example, is pointed out as affecting the entire population, regardless of the economic situation of the citizens. A temperature inversion affects everyone’s eyes and bronchopulmonary system. The pollution of the rivers makes them unusable as a source of drinking and leisure water. The pollution of the water table ends up contaminating the irrigated vegetables with this water. The depletion of the ozone layerin the atmosphere would increase the radiation load on everyone. Thus, pollution would not respect socioeconomic boundaries ; it would be a truly egalitarian and democratic plague.

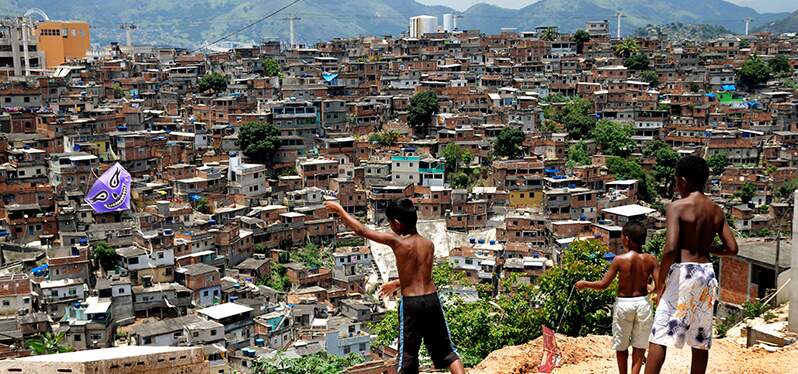

But the consequences of environmental pollution for human beings are not equally distributed among the population . Not everyone runs the same risk of having children born with disabilities, suffering from bronchial problems or drinking contaminated water. So what determines who will bear the physiological damage from environmental pollution ? What are the groups , categories , economic classes that are affected?

It is not difficult to recognize that, in these situations, it is the economically disadvantaged classes that are exposed to pollution. It is the same social class structure that determines the distribution of wealth, opportunities for social ascension, access channels to decision-making centers, which also determines the distribution of pollution in society.

Even in cases of seemingly universal effects, the chain of cause and effect needs to be examined more closely . The consequences of air pollution, of a thermal inversion, for example, on the human organism, are moderated by the state of the individual. As is known, the level of nutrition , working and housing conditions and difficult access to the medical-hospital system are factors that contribute to this situation. Pollution is yet another factor in this painful equation, and it contributes its share to the deterioration of people’s well-being.

The Constitution of the Republic of 1988 – in tune with the Magna Laws of industrialized countries and sensitive to the innovations of mass societies, communication and technology – structure, in the caput of art. 225, the protection of the environment , litteris :

“Art. 225. Everyone has the right to an ecologically balanced environment, an asset for common use by the people and essential to a healthy quality of life, imposing on the Government and the community the duty to defend and preserve it for present and future generations” .

Interpreting such a device, we found the presence of a right that goes beyond the individual, characterizing itself as transindividual , and more, of a diffuse nature, belonging to all , in an indistinct way . Three important aspects brought in the caput of art. 225, for the protection of the environment, also deserve emphasis: the ownership of the environmental asset , intergenerational responsibility and the participation of the community .

As for the ownership of the environmental good, the Constitution says that it is a good for common use by the people , therefore, intended for collective use , and cannot be appropriated by anyone. Di Pietro (1999) referring to the common use of the people defines them as “those that, by legal determination or by their own nature, can be used by all under equal conditions, without the need for individualized consent on the part of the Administration ”.

In our opinion, the legal nature of the environmental good is an important foundation to support the peculiar attribution of the Public Prosecutor’s Office in supervising administrative action in the process of socio-environmental intervention of any nature. This is not interference or intervention by the prosecutor, but a constitutional duty.

It must be remembered that environmental resources are finite . Therefore, interconnected with the notion of sustainable development , which is made for the future, since the use of environmental goods should provide future generations with at least the same quality of healthy life that we have today. This is the intergenerational responsibility .

Thus, making the natural system compatible with the social system, providing the ecological balance of the environment is the greatest challenge for public agencies or members of the community in the defense of the environment. The guardianship enshrined in the Maximum Law requires popular participation. Experience demonstrates that the effectiveness of protecting environmental heritage is directly proportional to the awareness , education and participation provided by the environmental citizenship movement.

Participation is not a concession from the law or from the administrator, participation is a construction whose basis is the ideal of society that people want for themselves and those who will succeed them. In the words of Demo (1993), “There is not enough and not finished participation”.

In the items and paragraphs of art. 225 of CF/88, the constitutional legislator established the instruments to ensure the effectiveness of the right to a healthy environment . As Benjamin (RT, 1993) emphasizes, “the so-called environmental function permeates the orbit of the State and calls the citizen, individually or collectively, to carry out some of its missions…”

Therefore, the conclusive arguments about the contribution of environmental justice demonstrate that the concept is favorable to the analysis of sustainable regional development , as it allows checking environmental issues addressed to the State in the order of civil rights and alerts us to the complexity of relations between the Public Power and Civil Society in the dynamics of events. The technical, professional, scientific and ideological differentiation of State agents is such that there is no simple equation between the hegemonic forces in society, State intervention and its concrete presence in the daily lives of citizens.

The instrumentalization of environmental law in the context of “environmental justice as a social practice” will take place when the State, as a mediator, translates the population’s “tensions” into intervention guidelines by its respective bodies. With the main objective of responding to the pressing demands of the population and for their benefit.

Evidently, none of this guarantees that public bodies effectively and primarily serve the interests of the population in general, and not the interests of politically and economically dominant groups . But it suggests that there is no determined path between these hegemonic interests and the daily activities of these institutional bodies, such as the Public Ministry, since the field of democratic disputes already shows organized groups of the most varied types.

Environmental justice can only be properly addressed when this happens. Nor is it the case to disqualify the actions of these groups with economic advantage and parties as ways of exercising citizenship. On the contrary, in a complex society like the Brazilian one in this 21st century, citizenship does not take place as a direct relationship between the individual and the State – it is in this interim that political science is manifested when analyzing how power is distributed –, the collective forms of claims, channeling information, and fulfilling fundamental civil rights .

For the discussion about the environmental frontier , Mukai (2002) points out that “in environmental matters, municipal and state legislation cannot go against federal law”. The notion of hierarchy of laws is linked to the supremacy of the Constitution. Incidentally, each state has its own Constitution and a set of state laws, which must conform to the federal ones . Likewise, municipalities, when preparing their organic laws and other laws, must comply with them so as not to conflict with State and Federal Law.

It is the majority understanding in the doctrine that environmental protection standards are of general interest , intended to regulate the matter at the national level, in the same way as all matters of collective interest – which goes beyond many of the understandings about borders presented in this effort. understanding of what is meant by environmental justice .

Always alluding to the struggle for the environment, we walk towards justice, perhaps the greatest of all, that of human sustainability.

Carla Rocha Sousa – Specialist in Social Development at Synergia

References

BENJAMIN, Antonio Herman (org.). Environmental damage : prevention, repair and repression. São Paulo: RT, 1993, p. 237-249.

DEMO, Peter. Participation is an achievement: Notions of participatory social policy . Ed. Cortez: São Paulo, 1993. 2nd edition. p.21.

DI PIETRO, Maria Sylvia Zanella. Administrative Law . Atlas Publisher: São Paulo, 1999. 10th. Edition. P. 437.

FIORILLO, Celso Antonio Pacheco. Brazilian Environmental Law Course . Editora Saraiva: São Paulo, 2017. 18th edition.

LEONEL, M. The Social Death of Rivers . São Paulo: Perspectiva, Institute of Anthropology and Environment: FAPESP, 1998 (Col. Estudos, 157).

MUKAI, Toshio. Systematized Environmental Law . 4. ed. Forensics: Rio de Janeiro, Universitária, 2002. p. 21.

Sign up and receive our news.